Erin Despard: Artist in Residence update

Shared by UBC Botanical Garden

Plant Propagation for the People:

A Community Design Process

This past summer, as part of my residency on the art of plant propagation, I worked on a community design project with Jingzhou Sun, a graduate student from UBC’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. I initiated this collaboration with the idea that propagation should be an accessible, everyday practice that anyone can do, rather than something practiced mainly by expert gardeners. This is not such a radical idea—after all, it used to be a required skill for doing any gardening at all. However, propagation requires two things that are currently in very short supply for many people—that is, time and social connections. Getting people to do it is not only a question of accessibility, but also inspiration.

In addition to this practical motivation, I was also interested in exploring a collaborative design process as a way of thinking creatively about the practical and social dimensions of propagation. What are the assumptions and constraints built into our existing tools and how might we re-frame the problems they were designed to address? This blog post will describe the process we went through, what we learned, and what I think is inspiring about the devices Jingzhou designed.

The Design Process

We began the project with two main objectives. The first was practical: to design two devices that would inspire more gardeners on the UBC campus to try propagating their own plants and thereby, to reduce the plastic waste often associated with home gardening (e.g., plastic pots, bedding packs). The second was more conceptual: to reimagine propagation as an educational as well as horticultural activity. How might growing one’s own plants inspire a different perspective on gardening in general? Before Jingzhou began his work on the preliminary designs, we undertook two forms of background research.

First, we read about the history of propagation and reviewed existing tools and techniques. Interestingly, most of these have not changed very much over the last 150 years. Many, such as the practices of forming soil blocks and using hot compost beds to support growth of young seedlings, are much older than that. We were inspired by the way these traditional techniques make use of natural relationships and processes. In contrast, technologies such as greenhouses and other enclosures increase the gardener’s control over those processes in order to increase propagation success. As Jingzhou observed however, they also set up a potentially problematic relation to the natural world—one in which we can tend to plants in certain enclosed spaces (e.g., greenhouses) without necessarily noticing the declining health of the broader environment. In light of our interest in educational potential, we decided that a good overarching strategy for the design process, would be to bring the circularity implied in traditional techniques together with the increased success that greenhouse technologies offer.

The second form of research we undertook was to survey campus community gardeners about their propagation needs and interests. Those who responded were most interested in methods using seeds or cuttings. We also learned that many of them had significant constraints on the time and space available for propagation; some had concerns with cost; and most had only one or two contacts with whom they could exchange plant materials. On the basis of these observations, we identified three additional parameters to guide Jingzhou’s design work: he should 1) provide at least one device that worked in a small space; 2) ensure that both the devices worked even if left unattended for a day; and 3) prioritize re-used materials. We addressed the final observation (lack of gardening contacts) in designs for an additional, community-oriented device.

The three devices we selected for development from Jingzhou’s preliminary sketches are presented below. So far, we have tested the first two devices in different settings, and shared all three designs in two propagation ‘zines’ distributed to community members. Next spring, we hope to do more testing and promotion of the devices on campus.

The Devices and What We Learned From Them

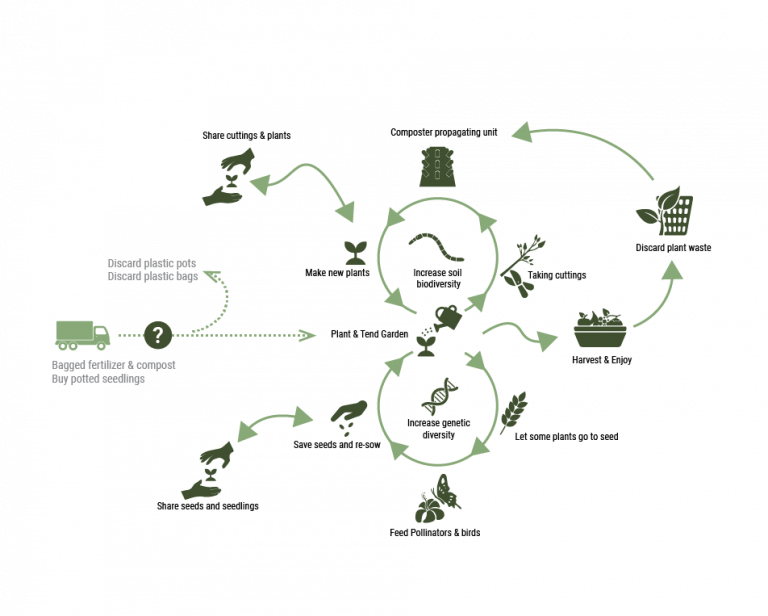

Probably the most important thing we learned from this process, was due to our decision to integrate traditional techniques in our designs. That is: propagation is not just a way to reduce waste and save money; it has the potential to support multiple relationships of circularity in home gardens. This is particularly clear in the practice of seed-saving, where plants left to flower nourish pollinators and birds while also benefiting from them in turn (via pollination and the distribution of seeds). With other methods, such as propagation by cuttings or divisions, gardeners may contribute to the establishment of new forms of circularity, since these methods require the sharing of plant materials between gardeners. To the extent that such exchanges become normalized or inspire other forms of reciprocity over time, they can give rise to circular social relations.

To put it another way, propagation has the potential to multiply, not only plants, but connections between gardeners, local environments and their communities. Further, it does this while reducing external inputs and outputs—many of which generate negative social and environmental effects at a distance (e.g., emissions from the transportation of plants and plastic pollution from single-use containers). We started to see the devices as part of a complex network of overlapping circular processes; they were nodes at which relationships that might be obscured by devices such as greenhouses or propagating cases, could be made visible.

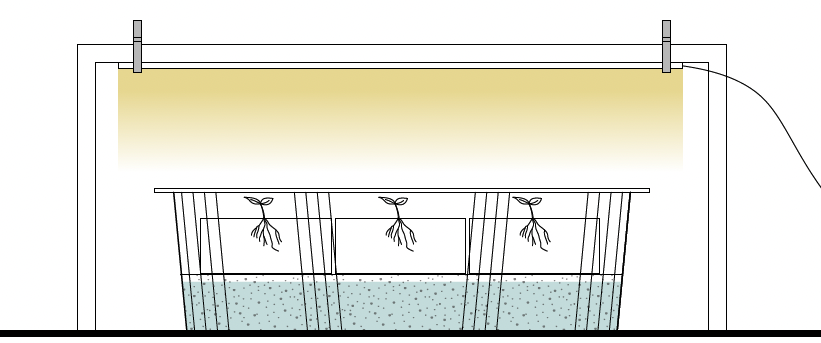

Our Propagation Case, for example, is an adaptation of the kind of plastic covered tray that many gardeners use, but it is made from a re-used clamshell container; instead of individual plastic cells, it makes use of soil blocks positioned on top of a bed of course sand. The surprising integrity of these blocks, particularly as the roots grow and bind the soil, is a subtle but powerful way to visualize the soil’s capillary action. It also demonstrates that the holding and moisture-retaining qualities of plastic are not as irreplaceable as we might think.

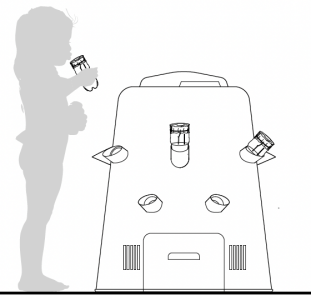

Similarly, our combination Composter-Propagator, takes the principle behind hot beds and pairs it with mini greenhouses (i.e., re-used beverage bottles inserted into the sides of a backyard composter). The heat produced by decomposing materials inside the composter speeds the growth of roots on plant cuttings, while also bringing attention to the action of otherwise invisible bacteria within the soil.

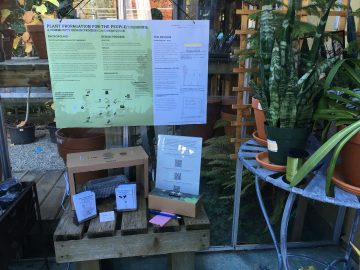

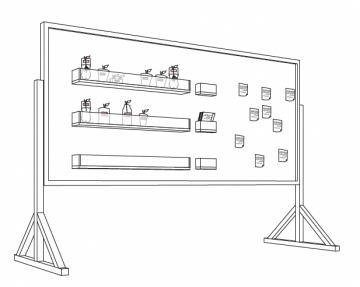

Finally, our Propagation Bulletin Board—which includes shelves on which gardeners can leave cuttings or rooted seedlings, as well as a message board—uses a familiar piece of community infrastructure to visualize the role of social contacts and communication in the propagation of plants.

Designing for a Future Community of Propagators

As we worked with prototypes of the first two devices and considered options for building the third, I came to appreciate that all three devices are more radical than they seem on first glance. This is because, achieving environmental control through methods that are cheaper, more sustainable and supportive of circular relationships, requires changes in human behavior. Some of these are minor (e.g., the seed-starting case, which requires that you spend time forming soil blocks instead of shopping for plastic seed trays), while others are more substantial. The composter-propagator for example, requires that you coordinate the taking of cuttings not only with seasonal changes in plant growth, but also the collection and assembly of different kinds of garden waste.

Any change that involves an investment of time or attention is difficult to make in a society organized around competition and narrow definitions of productivity. Our devices invite gardeners not just to make their own plants, but to participate in relationships with beings and processes or people with whom they might not otherwise have a connection. In some cases, theses are relationships that must be invented or re-invented. The bulletin board, for example, presumes a community of propagators, but this does not yet really exist, at least not in the geographically-concentrated sense that a bulletin board implies.

Through our efforts to educate and connect people as well as facilitate propagation, we envision a community in which it is common to make plants and in which circularity and cooperation are shared values as opposed to idealized concepts that require explaining. Our devices imagine a world in which the values that currently motivate so many of our choices—ease, convenience, novelty, instant gratification—are replaced, or at least disrupted, by others: a more nuanced knowledge of plants, an abundance of birds and pollinators, the ability to give and receive gifts. While it is far from a straight or even continuous line from one set of values to the other, in the space between them, we hope that something new and worthwhile might nonetheless begin to take shape.

Want to join the Propagation for the People community?

Follow us on Instagram (@propagationforthepeople) or Facebook (Propagation for the People Group).