Pandemic and Climate Change Stories

from Gardens BC

by Dr. Brian White and Khanh Le

Royal Roads University

School of Tourism and Hospitality Management

The past three years have defined a ‘new normal’ for public gardens internationally, as climate change and the pandemic impact garden visitation, revenue, and management. As in most jurisdictions, horticulturalists and managers responsible for public gardens in southern British Columbia have been dealing with Covid 19 and profound weather incidents, including extreme heat, drought, flooding, and strong winds. Gardens, both public and private, are a major BC leisure activity and visitor attraction, requiring consistent care and horticultural attention despite the recent garden closures and loss of revenue.

This study presents questionnaire survey results together with individual comments and stories from horticultural managers in public garden properties on southern Vancouver Island and the Lower Mainland of BC. Using evidence from stories recounted in video interviews, questionnaire data, and cross-referenced with secondary literature sources, a summary of resilient public garden crisis management strategies that emerged over the period 2020-2022 is presented, using a qualitative research approach.

Since the winter of 2020, public gardens around the world have been disrupted by Covid 19 restrictions and protocols. Garden access and events were cancelled, and the opportunity for the public to enjoy the physical and mental health benefits of public gardens ended during enforced lockdowns and stay at home orders. The uncertainty about re-opening public gardens and lack of revenue impacted gardens around the world. For example, only 4% of American public gardens remained open by the end of March 2020 (Forrest et al., 2020). The additional impact of severe weather events, including wildfires, excessive heat, particularly in urban situations, extreme cold and violent windstorms have made the situation even more challenging for the managers and staff of British Columbia’s public gardens.

Given the recent development of the Covid pandemic and unavoidably extreme weather, there have been very few studies of the recreational and emotional respite opportunities presented by accessible public gardens and green spaces within reach of urban and suburban populations. How were public gardens able to restore garden access to visitors while operating under such duress? Garden managers adaptive responses to the challenges encountered from the pandemic and the extreme weather are the central focus of this study, with an assessment of key learnings from an unprecedented series of events both from the primary data and from secondary sources.

Outdoor recreation in green spaces provides a setting for social interaction and shows immediate effects on psychological health and well-being (Gladwell et al., 2013). The maintenance of the gardens as an essential service where there are limitations on alternative outdoor settings is particularly important for elderly people with limited access to alternatives (Sugiyama et al. 2008) As the world starts to emerge from the pandemic, the urgent need for accessible green spaces in urban areas could reflect a substantial shift in urban planning priorities which has arisen from urgent public needs during the pandemic. This sudden rapid change in priorities is what is referred to by evolutionary biologists as punctuated equilibrium (Honey-Roses et al., 2021; Gould and Eldridge, 1993). The lessons learned for future pandemics and extreme weather events can be utilized from the experiences of the last three years.

There is the additional overlay of climate changes impacting public gardens that often feature unique plants vulnerable to extremes of temperature, and trees susceptible to strong winds. The responses which have been required from horticulturalists provide a blueprint for future pandemic and climatic scenarios and could expand the definition of ‘essential services’ to include horticulturalists. (Forrest et al., 2020).

The opportunity for outdoor recreation in accessible natural environments such as parks and public gardens has become more acute during the pandemic lockdowns, with extended lack of access to the health-related activities of walking, jogging, cycling, nature experience, and yoga. (Bherwani et al., 2021). As lockdowns were eased, gardens became venues of choice because many are adjacent to large urban populations, particularly in densely populated countries like India, where ‘90% of visitors admitted that urban green and open spaces help them cope with their physical and mental health concerns’ (Bherwani et al., 2021). The issue of access to green spaces and gardens has been explored as a serious global issue prior to the onset of Covid 19, where Americans spend 93% of their time indoors, often on their screens. In the UK, people spend an average of over eight hours a day on their devices (Li 2018, pp.34-35).

The public gardens have all required ongoing attention to sustain their collections during the pandemic, and while many gardens had to lay off staff, a core group has always been retained to manage critically important plant and facility management functions. As access to public gardens gradually reopened, public visitation increased again, in some cases very quickly as the public realized the value of public gardens as a safe place to get some healthy outdoor recreation. At the New York Botanical Garden, horticulturalists were identified as essential workers (Forest et al., 2020, p.4). However, because of Covid protocols and financial circumstances, re-staffing was frequently delayed, and the required garden workload tasks were assigned to workers who might not have specialized expertise (Forest et al., 2020, p.13). In many gardens, virtual and on-line activities were quickly expanded to provide for those unable to access the gardens (Castleberry, 2020, p.7).

The onset of the Omicron variant has, however, extended the ‘state of emergency’ for gardens around the world, delaying the re-opening of gardens and resumption of regular admissions, programs, and staffing. It does appear that the opportunities for private gardening in back yards or on allotments tended to promote horticultural pursuits in general and provided an impetus for visitation to public gardens after lockdowns and severe restrictions ended. For example, in a study that assessed the life satisfaction of garden and non-garden owners during the pandemic in Germany, Lehberger et al. (2021) found that garden owners had significantly better levels of life satisfaction and psychological health than non-gardeners. Germany left its public gardens and urban green spaces open and did not impose major restrictions. The study also indicated that there were significant socioeconomic differences in the two groups, including age and income (p.2). In that light, this study hopes to give gardens insight to sustain through tough times and continue to bring the beauty of nature and positive health impacts to the public.

Methodology

Bhat (2019) and Harvey (2020) indicate that secondary data increases the overall effectiveness of research when primary and secondary data are thematically compared and analyzed. Bengtsson (2016) suggests that a framework for data analysis must be based on to the primary research questions used to address a research problem.

In this research, interview and anonymous questionnaire responses to individual questions are represented in a repertory grid which illustrates responses to the research questions.

These responses are then analyzed to establish successful approaches which addressed the problems dealt with by public gardens in British Columbia in comparison to evidence from secondary sources.

Literature Review

Challenges from the Pandemic and Weather Events

British Columbia has been well-known for its beautiful gardens, especially around Victoria and the Lower Mainland. From historic to modern style gardens, visitors can come to BC to enjoy the “immersive and unique garden experiences” year-round (Gardens British Columbia, n.d.). When Covid-19 started affecting businesses in Canada at the beginning of 2019, these gardens were no exceptions. Many of them began with cancelling some events, and eventually closing doors to visitors (Castleberry, 2020; Forrest et al., 2020). Gardens in America went through the same phase; on March 16th, 2019, “more than 25 percent of gardens closed on a single day… and by the end of March, only 4 percent remained fully open to the public.” (Forrest, 2020).

Compared to other business, gardens were in an interesting situation during the first Covid-19 shutdown because they could not take a pause like the rest of the world. Plants kept on growing while flowers were blooming; therefore, horticulturists could not abandon their work. Many changes took place to create a safe working environment, such as reducing the number of staff or changing schedules, to limit contact; with the reduced staff and less to no volunteers, horticulturists had to take care of unfamiliar spaces and plants in their own gardens; only a few gardens were able to keep their staff as well as support from the volunteers (Forrest et al., 2020; Marwah et al., 2021; Hodor et al., 2021).

The day-to-day simply didn’t exist anymore…

Even though we had dealt with temporary closures after 9/11 and during various hurricanes and blizzards, none of us had ever experienced a long-term shutdown with no clear path to reopening. Gardens shouldn’t close in spring (Forrest et al., 2020).

With no visitors, most gardens did not have a stable source of income anymore; some of them experienced funding cuts as well. As a result, generating revenue was the main issue for a lot of gardens. To deal with this situation, in Latin America, many gardens connected with universities to reduce funding cost and to be recognized as academic institutions (Castleberry, 2020). At the same time in Europe, historic gardens went through major financial loss. In response, they implemented redundancy programs and brought down bonuses or base salaries; some gardens that were solely based on visitors and events for income began to source additional funding. (Hodor et al., 2021).

While most activities at the gardens were paused, virtual engagement was increased, mostly on social media (Castleberry, 2020, Hodor et al., 2021). Gardens used these platforms to share stories, pictures, updates of they daily operation behind closed doors – gardeners catching up on maintenance project while flowers showing off their beauty in the sun (Castleberry, 2020, Hodor et al., 2021). Through the same channel, staff, volunteer, and visitors showed their hopes for garden reopening (Castleberry, 2020, Hodor et al., 2021).

Content analyses demonstrated that the largest reach and activity of social media users were reached by accounts on the current state of the garden (it was the time of spring and early summer in Europe) or content regarding garden history. It is an important insight into the significant potential of the virtual world for information and awareness-raising regarding the existence, character, and value of garden patrimony (Hodor et al., 2021).

When gardens slowly reopened at the beginning of May of 2020, they implemented multiple changes and new procedures to avoid overcrowding, reduce in-person interactions, and ensure the safety of their team members and visitors. For gardens in America, event tickets were sold in timeslots; one-way paths were implemented; opening hours were extended to accommodate more visitors (Forrest et al., 2020). These changes were mentioned in the recommendations on how to maintain access to parks and green spaces during Covid-19, or any future transmissible disease outbreaks. Researchers proposed the following short-term recommendations:

• Control the flow of visitors using timeslots or structured schedules;

• If needed, utilize staff from other departments to ensure guidelines and rules are followed;

• Arrange exclusive visits to green spaces for vulnerable populations;

• Adjust park fees basing on different needs;

• Aim for “best practices in balancing expanded access with strategies to control the number of visitors” when making changes to the schedules or fees (Slater et al., 2020).

In addition to the pandemic challenge, gardens experienced severe weather in the past year, including strong wind, heavy rain, drought, and the heat dome (Hodor et al., 2021; Forrest et al., 2020).

The forecast was for a straight-line wind, but the tree branches were swirling in circles. The tops of the tall oaks and tulip poplars swayed in an unnatural dance… Watching the wind and rain, I suddenly heard a loud, splintering crack followed by an earthshaking crash. I squinted through the gray deluge and could see an enormous oak was missing from the skyline (Forrest et al., 2020).

In British Columbia specifically, the extreme weather was significantly noticeable in 2021: the 11-day heat dome in June with the record-high temperature of 45C; the driest summer in 75 years; four heat waves between May and August; “flood of floods” in November (Chung, 2021). The garden columnist Brian Minter believed that “after the extremes of 2021, nothing, in terms of weather, should surprise us in the year [of 2022] (Minter, 2022).” Observing the same extreme weather patterns happening with the cold spell in early 2022, Minter foresaw the record cold and hot moving further apart (Minter 2022).

The Positive Change

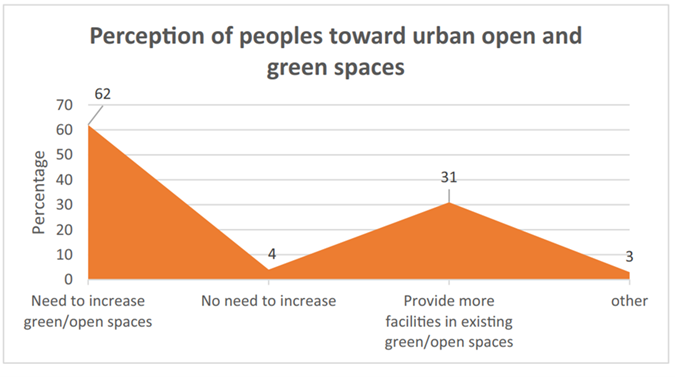

While the pandemic and the severe weather created interruptions to visitation, the demand for open and green spaces seemed to increase. Across the world, the recorded number of visits to the open green spaces was higher after the lockdown and with the distancing restrictions in effect (Bherwani et al., 2021; Grima et al., 2020; Honey-Rosés et al., 2020). In India, the same finding applied to those who did not visit open green spaces often before the lockdown. More people engaged in yoga outdoors and other health-related activities as they saw the benefit of green spaces on their physical and mental health (Bherwani et al., 2021). (Figure 1).

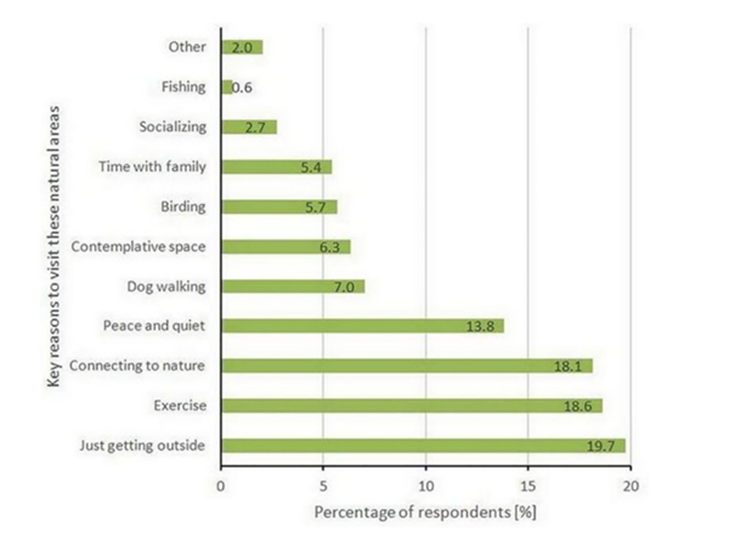

In a study on urban natural areas during Covid-19, people in Vermont, USA, mentioned various purposes of use of these spaces (see figure 2). All the activities mentioned in figure 2 “—have been shown to reduce stress” (Grima et al., 2020). The outdoor natural environment can provide not only mental but also physical health benefits; for example, resisting heart disease, stroke, obesity, mental fatigue, or stress. (Slater et al., 2020; Gladwell et al., 2013).

The response of British Columbia’s public gardens

Primary research results

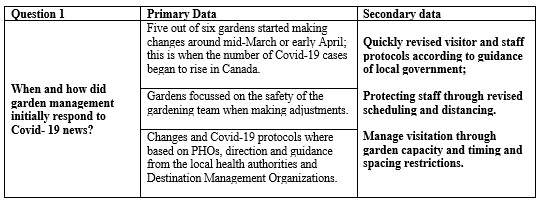

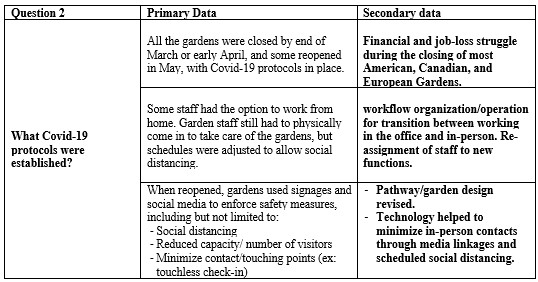

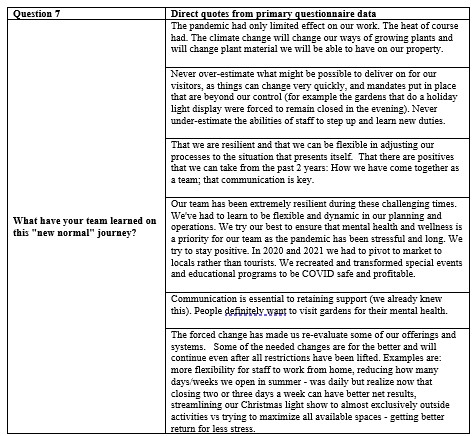

Bhat (2019) and Harvey (2020) indicate that secondary data increases the overall effectiveness of research when primary and secondary data are thematically compared and analyzed. Bengtsson (2016) suggests that a framework for data analysis must be based on to the primary research questions used to address a research problem. In this research, anonymous questionnaire and interview responses to individual questions are represented in a repertory grid which illustrates quoted responses to the research questions. These responses, which include quotes from questionnaire responses, are then cross-referenced to international papers outlining garden management approaches in jurisdictions outside of British Columbia. A concluding analysis outlines the widely shared approaches that can be used to address garden management in the ‘new normal’.

Questionnaires were sent to (8) garden managers belonging to Gardens BC, with (6) responses. Four interviews were conducted using the same questions, but with flexibility to allow for additional perspectives to be presented. Different respondents were selected for the questionnaires and the interviews.

Questionnaire/interview guide

Covid-19: 7 questionnaire and interview questions

- When and how did garden management initially respond to Covid- 19 news?

- What Covid-19 protocols were established?

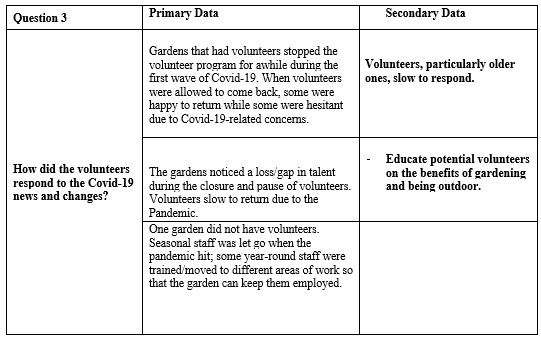

- How did the volunteers respond to the Covid-19 news and changes?

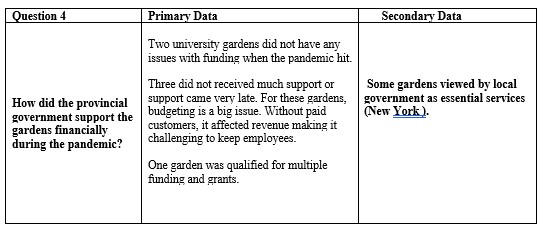

- How did the provincial government support the gardens financially during the pandemic?

Climate change questions

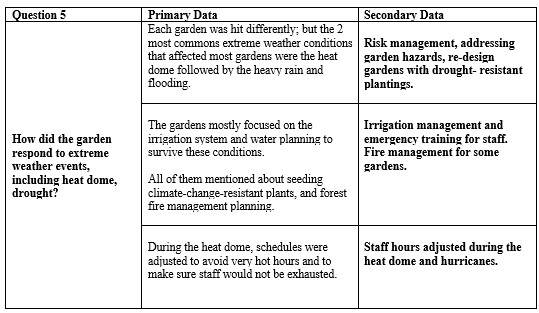

- How did the garden respond to extreme weather events, including heat dome, drought?

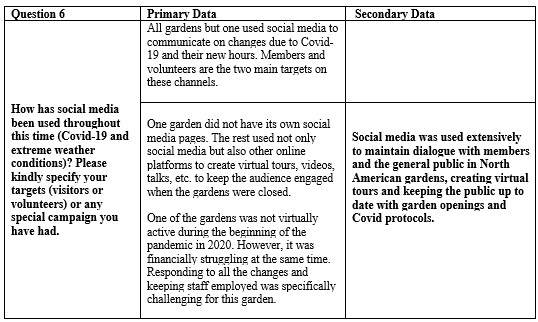

- How has social media been used throughout this time (Covid-19 and extreme weather conditions)? Please kindly specify your targets (visitors or volunteers) or any special campaign you have had.

- Dealing with the ‘New Normal’?

Data Analysis

The primary data below was collected through anonymous surveys and video interviews, and the secondary data through a review of literature. Six gardens responded to our surveys, and four garden managers agreed to be interviewed. Some direct quotes from the questionnaires are included.

Direct quotes (question 3):

- Many of our volunteers are still apprehensive about coming back.

- Those returning were very grateful to be back, working in the garden, and connecting with fellow volunteers.

- As vaccines became available more and more volunteers returned. That said, even during summer of 2021, several volunteers still held off returning to their positions due to concerns of getting Covid-19.

Direct quote (question 4):

- Provincial assistance was extremely slow, and tourism was not prioritized as it should have been, considering the number of people throughout the province it employs.

Direct quotes (question 5):

- From my own unscientific observations, these extreme weather events take a toll on plants that can’t adapt quickly to such extremes.

- We cannot control the weather, but we do have some control over our gardens. Maintaining healthy fertile soil, growing plants with similar needs together, planting more drought-tolerant plants and practice smart watering will help our plants adapt and thrive.

- We’ve tried to add timers as much as possible so watering in some areas is automated, but many areas are not on the system so there is a lot of hand watering done which takes a lot of staff time and resources.

- We are now having to look at much more active management of the forest and will be conducting a wildfire risk assessment this spring which will be followed by a prescription strategy.

Summary

Based on the comparative analysis of secondary and primary data there appears to be consistency on North American garden responses to the pandemic and extreme weather events over the past two years. In Europe and Asia there were more varied responses with gardens staying open, in Germany, for example.

Consistent with American gardens, the responses to Covid-19 in the participating BC gardens involved initial shut-downs and focus on staff and visitor protections. Social distancing through timing and spacing of visitors, re-scheduling and re-assignment of staff, and enhanced social media communications were instituted with guidance from local health authorities.

Across North American gardens, volunteers were often reticent to return as new Covid variants emerged, particularly threatening older volunteers. Gardens kept in touch with both volunteers and members using social media.

The provincial government was inconsistent in its financial support, tending to focus on the larger internationally significant gardens. In the USA, some gardens were deemed essential services and received support. Financial support in BC was seen as very late in coming by three gardens.

Social media was used extensively to maintain dialogue with members and the general public in North American public gardens, creating virtual tours and keeping the public up to date with garden openings, on-line events, and Covid protocols. It appears that the virtual tour has become a popular and effective communication tool for public gardens and will continue to enhance the garden experience.

In response to the extreme weather events that impacted many gardens across North America, staff and visitor protection and plant maintenance were seem as paramount no matter what type of extreme weather was being encountered. Adjustments to future drought, flood conditions, or extreme cold will have a wide impact on the plantings and garden design for North American gardens. Crisis management plans for public gardens will likely be a priority going forward.

The evidence provided here reinforces the significant role public gardens play as a health and wellness opportunity, particularly in urban areas where access to outdoor leisure is often restricted. The rapid expansion of virtual tours, talks, and information provides an additional marketing and ‘virtual experience’ for potential garden visitors, and it is to be hoped that public gardens will be viewed as an essential service for outdoor leisure experiences in the future.

References

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nursing Plus Open, 2, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

Bhat, A. (2019). Research Design: Definition, Characteristics and Types. QuestionPro https://www.questionpro.com/blog/researchdesign/

Bherwani, H., Indorkar, T., Sangamnere, R., Gupta, A., Anshul, A., Nair, M. M., … & Kumar, R. (2021). Investigation of Adoption and Cognizance of Urban Green Spaces in India: Post COVID-19 Scenarios. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 3, 100088.

Castleberry, K. (2020). The Impact of Covid-19 on Botanic Gardens Globally. Journal of Botanic Gardens Conservation International, 17(2), 7-8.

Chung, Emily. (2021, December). 10 weather stories that made 2021 a year like no other. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/top-10-weather-stories-2021-1.6288139

Forrest, T., Galligan, B., Gott, R. C., Guidarelli, C., Henrichsen, E. T., Huang, T., Kartes, N., LaPlume, G., Loving, S., Merriam, D., Salyards, J., Shearer, K., & Williams, K. (2020). Essential gardening: public gardens in the spring of covid-19. Arnoldia, 78(1), 16–31.

Garden British Columbia. (n.d.). Explore beautiful B.C. gardens. https://gardensbc.com/

Gladwell, V. F., Brown, D. K., Wood, C., Sandercock, G. R., & Barton, J. L. (2013). The great outdoors: how a green exercise environment can benefit all. Extreme physiology & medicine, 2(1), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-7648-2-3

Grima, N., Corcoran, W., Hill-James, C., Langton, B., Sommer, H., & Fisher, B. (2020). The importance of urban natural areas and urban ecosystem services during the COVID-19 pandemic. PloS one, 15(12), e0243344. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243344

Hodor, K., Przybylak, Ł., Kuśmierski, J., & Wilkosz-Mamcarczyk, M. (2021). Identification and analysis of problems in selected european historic gardens during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(3), 1332.

Honey-Rosés, J., Anguelovski, I., Chireh, V. K., Daher, C., Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C., Litt, J. S., … & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on public space: an early review of the emerging questions–design, perceptions and inequities. Cities & Health, 1-17.

Marwah, P., Zhang, Y. Y., & Gu, M. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 on the Horticultural Industry.

Minter, B. (2022, January). Brian Minter: Dealing with extreme weather patterns is becoming the norm. Vancouver Sun. https://vancouversun.com/homes/gardening/brian-minter-dealing-with-extreme-weather-patterns-is-becoming-the-norm

McQuarrie, John. (ed). (2022) Gardens Canada: Live the Garden Life. Canadian Garden Council, Ottawa.

Slater, S. J., Christiana, R. W., & Gustat, J. (2020). Peer Reviewed: Recommendations for keeping parks and green space accessible for mental and physical health during COVID-19 and other pandemics. Preventing chronic disease, 17. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.200204PMID: 32644919

Watch the video on the Gardens BC News & Blog: ‘The Resilience of BC Gardens’